Hot off the press today, I have calculated the skill of the PDO forecasts produced by some of the leading seasonal forecast models. This is of interest because the PDO is a primary mode of climate variability, and seasonal forecasts - especially for Alaska - often depend on expectations for the PDO phase in the coming months.

I looked at each of the models in the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) as well as the ECMWF seasonal forecasts. For each model, I calculated the PDO index from the monthly sea surface temperature forecasts from 1982-2010; these are retrospective forecasts that are provided to help with model bias correction, forecast calibration, and skill assessment. The chart below shows results averaged over all months of the year, for 3 different lead times.

As we would expect, the ensemble mean of the NMME models (i.e. all but ECMWF) provides the most skillful prediction of the PDO index and is better than even the best individual model; this is why we look at multi-model ensembles. However, the ECMWF is not far behind in terms of skill, and the CMC2 model is also good. Interestingly, the CFSv2 (NOAA's climate model) is the worst model by some margin; this is a big surprise to me, because I have a high regard for CFSv2 on the whole. Further investigation will be needed to see if there is a particular area of the North Pacific where the CFSv2 temperature forecasts are poor.

Looking at the breakdown of skill by month, the winter PDO index is relatively easy for the models to predict, and the early summer season is the most difficult - see below. This is not too surprising because the winter PDO is linked to tropical Pacific conditions, which the models are quite good at predicting; but the models notoriously struggle with ENSO evolution through the "spring predictability barrier".

Here's the most recent PDO forecast from the same set of models. NCAR's CESM model is an outlier with its very strongly positive PDO phase, but this is one of the less good models according to the skill statistics.

Objective Comments and Analysis - All Science, No Politics

Primary Author Richard James

2010-2013 Author Rick Thoman

Saturday, October 29, 2016

Friday, October 28, 2016

October Temperature Contrast

There will be much more to say about this once all the October numbers are in, but there's no doubt that Arctic Alaska and the wider Arctic region have seen extraordinary and record-breaking warmth this month. The chart below shows the updated season-to-date accumulation of freezing degree days in Barrow: the total is now up to a meager 78 FDDs. The previous record lowest through this date was 128 FDDs in 2012 (data from 1930-present).

The mean temperature so far this month in Barrow stands at 30.2°F, and with a chance of rain (plain, not freezing) in the forecast, that number isn't going to drop much by the end of the month. Sea ice is nowhere near Barrow, and the Arctic-wide ice extent is at record low levels.

In contrast, clear skies and light winds in Fairbanks have produced strong inversion conditions as surface temperatures have turned rapidly cooler - we might say winter had a sudden onset this year. Season-to-date FDDs are now higher than the past 3 years at this date and are close to the long-term normal.

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

North Pacific Blob Update

I posted an update on the Alaska "Blob Tracker" blog today:

https://alaskapacificblob.wordpress.com/2016/10/26/subsurface-conditions/

https://alaskapacificblob.wordpress.com/2016/10/26/subsurface-conditions/

Monday, October 24, 2016

Clear and Colder

With a little snow now on the ground and nights continuing to lengthen rapidly, temperatures have dropped sharply under clear skies in the past few nights. Last night was the coldest yet, with temperatures below -15°F in quite a number of locations in the eastern interior. Here are a few of the coldest measurements so far:

-24°F Bolio RAWS at Fort Greely

-22°F Chicken COOP

-20°F Tok #2 COOP

-17°F Circle Hot Springs COOP

-16°F Salcha RAWS

-12°F Northway AP

The coldest spot around Fairbanks seems to have been the sensor near Smith Lake on UAF's North Campus, which reached -13°F yesterday and -12°F today. Fairbanks airport dropped below 0°F for the first time yesterday; this is just slightly earlier than normal.

The cold is not particularly unusual for the time of year, but the persistence of clear skies this month certainly is very unusual. In just the past 2 weeks, Fairbanks has seen sunny and very warm weather (55°F on the 12th), sunny and windy weather, and now sunny and calm, cold weather. The absence of cloud is remarkable, because this is normally one of the cloudiest times of year in Fairbanks (only early August is comparable). Including today, 19 of 24 days so far in October have had less than 50% cloud cover on average, and this is easily a record for the entire month - the previous highest total was 10 of 31 days in 2009 (based on ASOS data since 1998).

The reason for the clear skies is plain to see in a reanalysis estimate of 500mb heights so far this month: an axis of high pressure has extended from the northeastern Pacific to northwestern Alaska and the Chukchi Sea.

Compared to normal, upper-level pressure has been well above normal to the northwest, and so the usual westerly flow across interior Alaska has been blocked. Obviously this also explains the lack of precipitation; the light snowfall last week produced a mere 0.02" of liquid equivalent precipitation - the month's only precipitation. The driest October on record in Fairbanks was 1954, with 0.08".

Here's the October 1-22 average relative humidity at 850mb, according to the NCEP/NCAR reanalysis: there's a large zone of sub-45% values across the interior.

The departure from normal shows where the dry conditions aloft have been most unusual:

-24°F Bolio RAWS at Fort Greely

-22°F Chicken COOP

-20°F Tok #2 COOP

-17°F Circle Hot Springs COOP

-16°F Salcha RAWS

-12°F Northway AP

The coldest spot around Fairbanks seems to have been the sensor near Smith Lake on UAF's North Campus, which reached -13°F yesterday and -12°F today. Fairbanks airport dropped below 0°F for the first time yesterday; this is just slightly earlier than normal.

The cold is not particularly unusual for the time of year, but the persistence of clear skies this month certainly is very unusual. In just the past 2 weeks, Fairbanks has seen sunny and very warm weather (55°F on the 12th), sunny and windy weather, and now sunny and calm, cold weather. The absence of cloud is remarkable, because this is normally one of the cloudiest times of year in Fairbanks (only early August is comparable). Including today, 19 of 24 days so far in October have had less than 50% cloud cover on average, and this is easily a record for the entire month - the previous highest total was 10 of 31 days in 2009 (based on ASOS data since 1998).

The reason for the clear skies is plain to see in a reanalysis estimate of 500mb heights so far this month: an axis of high pressure has extended from the northeastern Pacific to northwestern Alaska and the Chukchi Sea.

Compared to normal, upper-level pressure has been well above normal to the northwest, and so the usual westerly flow across interior Alaska has been blocked. Obviously this also explains the lack of precipitation; the light snowfall last week produced a mere 0.02" of liquid equivalent precipitation - the month's only precipitation. The driest October on record in Fairbanks was 1954, with 0.08".

Here's the October 1-22 average relative humidity at 850mb, according to the NCEP/NCAR reanalysis: there's a large zone of sub-45% values across the interior.

The departure from normal shows where the dry conditions aloft have been most unusual:

Friday, October 21, 2016

Snow Cover - Will It Last

A fair portion of the interior now has at least a little snow on the ground after yesterday's modest snowfall. Half an inch of accumulation was reported at Fairbanks airport, but the snow depth was rounded up to 1". It's little more than a dusting of snow, so what are the odds that it will last and prove to be the start of the winter snow pack?

An analysis from a couple of years ago (see here) indicates that we're now late enough in October that there is less than a 20% chance that a one-inch snow cover will melt out to a trace or less. This suggests that this year is likely to be one of the 10% or so in which the first measurable snowfall doesn't melt out. On the other hand, the forecast for next week looks warm, with major storminess in the Bering Sea importing warm air over interior Alaska. About half of all years reach 40°F or warmer after October 25 in Fairbanks, so if it doesn't snow any more - which looks likely in the short-term - then I'd say there's a fair chance of seeing bare ground again.

The chart below shows the number of days with zero or trace snow cover occurring after the first measurable snowfall, versus the date of the first snowfall on the horizontal axis. Obviously the earlier the first snow occurs, the more subsequent snow-free days there tend to be before winter sets in. But it's interesting to see that very late first snows do tend to melt out - which makes sense if the weather pattern is unusually warm in those years.

The outlier on the lower left is from the infamous early winter onset of 1992 - the only time the winter snow pack was established in September, and mid-September at that.

An analysis from a couple of years ago (see here) indicates that we're now late enough in October that there is less than a 20% chance that a one-inch snow cover will melt out to a trace or less. This suggests that this year is likely to be one of the 10% or so in which the first measurable snowfall doesn't melt out. On the other hand, the forecast for next week looks warm, with major storminess in the Bering Sea importing warm air over interior Alaska. About half of all years reach 40°F or warmer after October 25 in Fairbanks, so if it doesn't snow any more - which looks likely in the short-term - then I'd say there's a fair chance of seeing bare ground again.

The chart below shows the number of days with zero or trace snow cover occurring after the first measurable snowfall, versus the date of the first snowfall on the horizontal axis. Obviously the earlier the first snow occurs, the more subsequent snow-free days there tend to be before winter sets in. But it's interesting to see that very late first snows do tend to melt out - which makes sense if the weather pattern is unusually warm in those years.

The outlier on the lower left is from the infamous early winter onset of 1992 - the only time the winter snow pack was established in September, and mid-September at that.

Thursday, October 20, 2016

MOS Forecast Bias

As Fairbanks awaits the much-delayed first accumulating snow of the season today (according to the NWS), I wanted to look back at the forecast discrepancy I noted a couple of weeks ago to see how things turned out. The chart below shows the automated computer forecasts of daily high temperatures from the GFS MOS product (black line) and the actual outcome in red. Note that I've taken the forecasts for "day 3", for example a forecast for Thursday's high temperature produced on Monday evening.

The results are amazing: the MOS forecast was about 18-20°F too cold for more than a week. Given the usually strong performance of MOS, the error is very surprising.

I've done some digging on potential causes for the problem, and there seems to be a partial answer in the way the MOS equations are developed. First, recall that the MOS (Model Output Statistics) technique uses multiple regression to estimate relationships between observed weather variables and predictors in the "raw" model forecasts (e.g. 850mb temperature). To better capture differences in the relationships between summer and winter, the equations are developed separately for April through September and for October through March (reference here); so the regression switches on October 1 and April 1.

What does this mean for Fairbanks? Well, the vast majority of days between October 1 and March 31 have snow on the ground, and so the "winter" model will reflect the physics of a snow-covered landscape; for example, when high pressure develops with low humidity and clear skies, the model will predict a substantial drop in temperatures. However, in the minority of cases when snow is absent, then the model forecast will be too cold. In other words, the model is effectively assuming snow cover to be present, although it does not use snow cover as a predictor.

This information partially explains the huge cold bias in early October this year, because the weather pattern was just the kind of set-up that is normally cold in winter - high pressure, clear skies, and low humidity. However, if the snow-cover explanation were completely adequate, then we would expect that similar errors would have occurred in other years with no snow cover in October. The charts below show the same analysis for selected years in the past.

First, in 2015 the MOS forecasts were too warm (as expected) during the period of unusual snow cover in late September and early October, but there was no obvious bias later in October after the early snow melted off.

October of 2013 was very unusual with its lack of snow, and MOS showed a modest cold bias then, but nothing like what we've seen recently.

Finally, I looked at two earlier years in which strong high pressure occurred in combination with zero snow on the ground during October. In 2003, high pressure aloft peaked at the beginning of October, and there was a slight cold bias in the forecasts - but nothing too alarming.

In 2009, a ridge of high pressure developed on about the 7th of October, and once again the MOS forecasts were too cold, but not drastically so. Bear in mind that the GFS model and the MOS equations have changed over time, so the comparison to 2016 isn't quite fair, but if anything the newer forecasts should be better.

In conclusion, it's still not clear what caused the enormous errors in the MOS forecasts recently. Part of the problem is that the winter MOS equations aren't suitable for predicting temperatures during snow-free conditions, but in previous years this hasn't caused a major issue. The good news is the NWS forecasters ably detected the recent bias in the MOS output and adjusted their forecasts accordingly. As a meteorologist myself, it's comforting to know there's still room to improve on what the computers provide.

The results are amazing: the MOS forecast was about 18-20°F too cold for more than a week. Given the usually strong performance of MOS, the error is very surprising.

I've done some digging on potential causes for the problem, and there seems to be a partial answer in the way the MOS equations are developed. First, recall that the MOS (Model Output Statistics) technique uses multiple regression to estimate relationships between observed weather variables and predictors in the "raw" model forecasts (e.g. 850mb temperature). To better capture differences in the relationships between summer and winter, the equations are developed separately for April through September and for October through March (reference here); so the regression switches on October 1 and April 1.

What does this mean for Fairbanks? Well, the vast majority of days between October 1 and March 31 have snow on the ground, and so the "winter" model will reflect the physics of a snow-covered landscape; for example, when high pressure develops with low humidity and clear skies, the model will predict a substantial drop in temperatures. However, in the minority of cases when snow is absent, then the model forecast will be too cold. In other words, the model is effectively assuming snow cover to be present, although it does not use snow cover as a predictor.

This information partially explains the huge cold bias in early October this year, because the weather pattern was just the kind of set-up that is normally cold in winter - high pressure, clear skies, and low humidity. However, if the snow-cover explanation were completely adequate, then we would expect that similar errors would have occurred in other years with no snow cover in October. The charts below show the same analysis for selected years in the past.

First, in 2015 the MOS forecasts were too warm (as expected) during the period of unusual snow cover in late September and early October, but there was no obvious bias later in October after the early snow melted off.

October of 2013 was very unusual with its lack of snow, and MOS showed a modest cold bias then, but nothing like what we've seen recently.

Finally, I looked at two earlier years in which strong high pressure occurred in combination with zero snow on the ground during October. In 2003, high pressure aloft peaked at the beginning of October, and there was a slight cold bias in the forecasts - but nothing too alarming.

In 2009, a ridge of high pressure developed on about the 7th of October, and once again the MOS forecasts were too cold, but not drastically so. Bear in mind that the GFS model and the MOS equations have changed over time, so the comparison to 2016 isn't quite fair, but if anything the newer forecasts should be better.

In conclusion, it's still not clear what caused the enormous errors in the MOS forecasts recently. Part of the problem is that the winter MOS equations aren't suitable for predicting temperatures during snow-free conditions, but in previous years this hasn't caused a major issue. The good news is the NWS forecasters ably detected the recent bias in the MOS output and adjusted their forecasts accordingly. As a meteorologist myself, it's comforting to know there's still room to improve on what the computers provide.

Monday, October 17, 2016

Windy and Colder

Strong winds have been blowing in Fairbanks since yesterday morning, as high pressure to the north is creating an intense pressure gradient across the state. The strong easterly flow has imported the season's first decently cold air mass, with 850mb temperatures dropping to -14°C above Fairbanks by yesterday afternoon. Saturday morning's balloon sounding revealed the first entirely sub-freezing temperature profile of the season in Fairbanks, and this is much later than usual - the normal date for this event is September 28, and the record latest was in 1969 (October 20). Fairbanks also recorded its first sub-freezing calendar day yesterday, with a high of 28° F - but no doubt it felt a good deal colder than that.

The graphics below show the sea-level pressure analysis (top) and 500mb height analysis (bottom) from 3pm AKST yesterday afternoon, courtesy of Environment Canada. The development of an upper-level high pressure system over Chukotka is consistent with the high-latitude blocking patterns and negative Arctic Oscillation that have been observed so far this month.

Here's a surface weather display from about the same time.

Webcam images from Ester Dome yesterday showed an abundance of blowing dust in the Tanana River valley as a result of the strong winds. The simple animation below shows the period when winds began to gust over 20 knots (23 mph) at Fairbanks airport; blowing dust was reported at the airport for several hours.

Sustained winds of 20 knots are quite unusual in Fairbanks at this time of year, as the following chart demonstrates. In the nearly 20 years since the ASOS platform began reporting at Fairbanks airport, there have been only 2 other occasions with 20+ knot winds in the month of October, and September and November have seen zero and 1 such event respectively. Winds like this are more commonly observed in late winter and spring.

In terms of wind direction, however, the current event (northeasterly winds) is much more typical in Fairbanks; the chart below shows that nearly all wind events of this magnitude are directed either from the northeast or from west to just south of west. However, the easterly component is rarely observed in summer: since 1998, all of the June-September strong wind events have come from the western half of the compass (and one from the north).

The graphics below show the sea-level pressure analysis (top) and 500mb height analysis (bottom) from 3pm AKST yesterday afternoon, courtesy of Environment Canada. The development of an upper-level high pressure system over Chukotka is consistent with the high-latitude blocking patterns and negative Arctic Oscillation that have been observed so far this month.

Here's a surface weather display from about the same time.

Webcam images from Ester Dome yesterday showed an abundance of blowing dust in the Tanana River valley as a result of the strong winds. The simple animation below shows the period when winds began to gust over 20 knots (23 mph) at Fairbanks airport; blowing dust was reported at the airport for several hours.

Sustained winds of 20 knots are quite unusual in Fairbanks at this time of year, as the following chart demonstrates. In the nearly 20 years since the ASOS platform began reporting at Fairbanks airport, there have been only 2 other occasions with 20+ knot winds in the month of October, and September and November have seen zero and 1 such event respectively. Winds like this are more commonly observed in late winter and spring.

In terms of wind direction, however, the current event (northeasterly winds) is much more typical in Fairbanks; the chart below shows that nearly all wind events of this magnitude are directed either from the northeast or from west to just south of west. However, the easterly component is rarely observed in summer: since 1998, all of the June-September strong wind events have come from the western half of the compass (and one from the north).

Thursday, October 13, 2016

Freeze-Up Progress - Or Lack of It

The situation in Barrow deserves another quick mention today, because it's so extraordinary - the warmth is unprecedented for the time of year in the modern observational record. There's no snow on the ground - not even a trace - and this is the latest date in the year when this has been observed (1920-present); and this isn't because it's been too dry, it's just been too warm. Not a single day so far this autumn has seen a high temperature below freezing, and we're now 9 days past the previous record in this respect. As the chart below shows, temperatures have not decreased at all in the last month - in fact the trend is slightly up.

Another perspective on the unprecedented warmth is to look at the accumulation of freezing degree days so far this season. Barrow has managed a grand total of 4.0 FDDs so far this autumn, which is easily the lowest on record (2012 had 24.0 through October 12). On the flip side, thawing degree days have accumulated at a record pace this month, with 24.5 TDDs for October 1-12. The chart below shows the numbers for each year since 1930 (click to enlarge).

Here's the current webcam photo from Barrow - no sea ice and no snow.

Another perspective on the unprecedented warmth is to look at the accumulation of freezing degree days so far this season. Barrow has managed a grand total of 4.0 FDDs so far this autumn, which is easily the lowest on record (2012 had 24.0 through October 12). On the flip side, thawing degree days have accumulated at a record pace this month, with 24.5 TDDs for October 1-12. The chart below shows the numbers for each year since 1930 (click to enlarge).

Here's the current webcam photo from Barrow - no sea ice and no snow.

Away from the warming influence of the Arctic (an odd concept, perhaps), freeze-up is beginning on interior rivers. The webcam photos below show the situation on the Yukon River at Dawson YT and at Beaver.

Tuesday, October 11, 2016

Excessive Warmth in Barrow

It's that time of the year again when Barrow's temperatures reveal the impact of the loss of Arctic sea ice when compared to what used to be normal in the latter part of the 20th century. Simply put, Octobers now are really warm relative to what they used to be, and there's little variance from year to year as the climate has become more or less maritime at this time of the year. However, this month is standing out even relative to recent warm years, as Rick has noted in recent messages on Twitter:

To facilitate the comparison to how things used to be, I created climatological normals of daily high and low temperatures for 1961-1990 and 2002-2015; October of 2002 was the first in the modern run of very warm Octobers. The chart below shows that the daily normals have risen for just about every day on the calendar, but the difference in October is most profound: from October 1 through October 29, the 2002-2015 normal low temperature is higher than the 1961-1990 normal high temperature.

Looking at the variance of daily temperatures, we find that the magnitude of daily variations has become much smaller from mid-September all the way through mid-winter, and this is especially true for daily maximum temperatures. The peak percentage difference occurs on October 10, when the standard deviation of high temperatures has dropped by over 50% between the two periods shown here. This is easy to understand physically: with sea ice now far to the north in October, it's just about impossible to get cold air into Barrow, so the lower part of the temperature distribution has been eliminated.

Here are some webcam photos from northern Alaska this afternoon, showing the relatively balmy scene.

Toolik Lake is still mostly open:

There's no snow on the ground at Kavik:

Teshekpuk Lake remains unfrozen, with bare tundra on the shore:

And there's just a little ice on one of the small lakes adjacent to Teshekpuk Lake:

Evidently the Colville River remains largely unfrozen at Umiat as well:

44F at #Barrow Monday is a daily record and a new record high temp for October. Old Oct record 43F in 1925 & 1954 #akwx @Climatologist49— Rick Thoman (@AlaskaWx) October 11, 2016

Monday was the warmest Oct day ever in Barrow with a high of 44ºF. The previous Oct record was 43ºF set 10/10/1925 and tied 10/3/1954. #AKwx pic.twitter.com/ia4Za5pWRm— NWS Fairbanks (@NWSFairbanks) October 11, 2016

More #Barrow records: warmest first 10 days of Oct, mean 33.9F. No days high ≤32F yet this fall, latest of record #akwx @Climatologist49— Rick Thoman (@AlaskaWx) October 11, 2016

October 11th: no snow on ground & no sea ice at #Barrow. 1998 only other year with zero SOG this late #akwx @Climatologist49 @DaveSnider pic.twitter.com/CyGXL7zPuK— Rick Thoman (@AlaskaWx) October 11, 2016

To facilitate the comparison to how things used to be, I created climatological normals of daily high and low temperatures for 1961-1990 and 2002-2015; October of 2002 was the first in the modern run of very warm Octobers. The chart below shows that the daily normals have risen for just about every day on the calendar, but the difference in October is most profound: from October 1 through October 29, the 2002-2015 normal low temperature is higher than the 1961-1990 normal high temperature.

Looking at the variance of daily temperatures, we find that the magnitude of daily variations has become much smaller from mid-September all the way through mid-winter, and this is especially true for daily maximum temperatures. The peak percentage difference occurs on October 10, when the standard deviation of high temperatures has dropped by over 50% between the two periods shown here. This is easy to understand physically: with sea ice now far to the north in October, it's just about impossible to get cold air into Barrow, so the lower part of the temperature distribution has been eliminated.

Here are some webcam photos from northern Alaska this afternoon, showing the relatively balmy scene.

Toolik Lake is still mostly open:

There's no snow on the ground at Kavik:

Teshekpuk Lake remains unfrozen, with bare tundra on the shore:

And there's just a little ice on one of the small lakes adjacent to Teshekpuk Lake:

Evidently the Colville River remains largely unfrozen at Umiat as well:

Saturday, October 8, 2016

Peak Climatological Cooling

First, an update on temperatures: the first 0°F observations this season occurred today at the usual cold spot of Chicken and also at the Chalkyitsik RAWS. Remarkably, the latter site had measured +1°F each of the 3 previous nights. Circle Hot Springs has been to 3°F and the Salcha RAWS made it to 4°F today. There was a bit of ice running on the Yukon River at Dawson, Yukon Territory, today, where the temperature has been struggling to get above freezing in recent days, even under clear skies.

We're approaching the date on the calendar when climatological normal temperatures drop most rapidly in interior Alaska; this occurs around October 24 in Fairbanks, at which point daily normal mean temperatures are dropping more than 6°F per week. Based on published normals, the station with the most rapid drop is Woodsmoke (7°F per week), as noted in this post from 3 years ago:

http://ak-wx.blogspot.com/2013/10/peak-cooling.html

The very rapid cooling at this time of year means it is quite likely that any given week will be cooler than the previous week in Fairbanks. But how likely is quite likely? I got to wondering about this, because of course any given day is only slightly more likely to be cooler than the last, but a full month is certain to be cooler than the last at this time of year. How do these probabilities vary with calendar date and with the length of the averaging period? The chart below answers this question, which I've been curious about for some time.

It's interesting to see that the rate of cooling in mid-October is so great that any given day is more than 60% likely to be cooler than the previous day, and any given week is 80% likely to be cooler than the last. It's still possible, though unusual, for consecutive 2-week periods to defy the seasonal trend, but by the time we get to 20-day periods this is virtually impossible - so for example, the last 20 days of October are nearly certain to be cooler than the 20 days prior.

Looking at calendar months, it's interesting to note that August has never been warmer than July in Fairbanks (although it's bound to happen one of these years), September has never been warmer than August (although remarkably in 1969 it came close), and of course October and November have never been warmer than the preceding months respectively. On the other side of the year, April, May, and June have always been warmer than the calendar months immediately prior.

An unrelated but surprising detail on the chart is that the series for consecutive single days (black line) doesn't drop below zero until early August: so even in late July, each day is more than 50% likely to be warmer than the previous day. This is inconsistent with the 1981-2010 normals, which show the climatological peak of daily mean temperature on July 3 in Fairbanks. More surprising still is that the other series don't show the same thing, so for example 10 day periods ending in late July are considerably more likely to be cooler than the one before. I suspect the anomaly for single days has to do with some skewness in the temperature distribution, but a bit more investigation would be needed to clarify this.

We're approaching the date on the calendar when climatological normal temperatures drop most rapidly in interior Alaska; this occurs around October 24 in Fairbanks, at which point daily normal mean temperatures are dropping more than 6°F per week. Based on published normals, the station with the most rapid drop is Woodsmoke (7°F per week), as noted in this post from 3 years ago:

http://ak-wx.blogspot.com/2013/10/peak-cooling.html

The very rapid cooling at this time of year means it is quite likely that any given week will be cooler than the previous week in Fairbanks. But how likely is quite likely? I got to wondering about this, because of course any given day is only slightly more likely to be cooler than the last, but a full month is certain to be cooler than the last at this time of year. How do these probabilities vary with calendar date and with the length of the averaging period? The chart below answers this question, which I've been curious about for some time.

It's interesting to see that the rate of cooling in mid-October is so great that any given day is more than 60% likely to be cooler than the previous day, and any given week is 80% likely to be cooler than the last. It's still possible, though unusual, for consecutive 2-week periods to defy the seasonal trend, but by the time we get to 20-day periods this is virtually impossible - so for example, the last 20 days of October are nearly certain to be cooler than the 20 days prior.

Looking at calendar months, it's interesting to note that August has never been warmer than July in Fairbanks (although it's bound to happen one of these years), September has never been warmer than August (although remarkably in 1969 it came close), and of course October and November have never been warmer than the preceding months respectively. On the other side of the year, April, May, and June have always been warmer than the calendar months immediately prior.

An unrelated but surprising detail on the chart is that the series for consecutive single days (black line) doesn't drop below zero until early August: so even in late July, each day is more than 50% likely to be warmer than the previous day. This is inconsistent with the 1981-2010 normals, which show the climatological peak of daily mean temperature on July 3 in Fairbanks. More surprising still is that the other series don't show the same thing, so for example 10 day periods ending in late July are considerably more likely to be cooler than the one before. I suspect the anomaly for single days has to do with some skewness in the temperature distribution, but a bit more investigation would be needed to clarify this.

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

Gradually Cooling Off

The coolest temperatures of the season so far were observed in the interior last night, with several locations dipping into the single digits - as befits the time of year. The Chalkyitsik RAWS dropped to +4°F, which is the lowest temperature observed so far in Alaska this season as far as I'm aware. Other lows included:

7°F Beaver Creek RAWS

8°F Circle Hot Springs COOP

9°F Eagle airport and RAWS

9°F Chicken COOP

At Fairbanks airport the first indisputably hard freeze occurred the night before, with a low of 22°F. Yesterday was also the first day with a daily mean temperature of 32°F. If these conditions were to continue, it wouldn't be long before some ice would be running in the rivers, but the forecast shows a warming trend.

[Update October 5: this morning was colder, with a low of +1°F at the Chalkyitsik RAWS and +4°F at Chicken. Closer to Fairbanks, the Goldstream Creek COOP had 11°F, and it was 9°F at the Salcha RAWS.]

Speaking of the forecast, I couldn't help noticing a major discrepancy today between the GFS MOS (automated computer) forecast and the rest of the guidance for Fairbanks. Here's this morning's MOS bulletin, with the "N/X" line showing low temperatures well down in the teens from Thursday through Monday, and with high temperatures staying near or below freezing for several days despite clear skies.

A quick look at this evening's NWS forecast for the airport shows a dramatically different picture, with high temperatures above 40°F and lows not far below freezing.

The GFS model forecast itself (from which the MOS output is derived) shows increasing warmth aloft in the next week, with 850mb temperatures rising well above freezing by Friday, and with very low relative humidity suggesting clear skies.

The raw model 2m temperature forecast shows conditions similar to the NWS forecast and drastically different from MOS.

So what's going on with MOS? Frankly I have no idea, but it's clearly wrong - and this is interesting, because MOS usually serves as a baseline or "first guess" for forecast systems; it is generally much better than raw model output, because it's a statistical regression based on historical observations. I briefly wondered if perhaps MOS is assuming there is snow on the ground already, but this is most unlikely as the historical probability of having snowcover in Fairbanks at this date is less than 20%.

To show how unlikely it is that Fairbanks will see a daily high temperature below freezing any time soon, we can look at how cold the upper-air temperatures need to be to produce a sub-freezing day. The chart below shows the afternoon 850mb temperatures on all such days from September 20 through November 19, beginning in 1957; we can see that 850mb temperatures are always well below freezing when daytime conditions remain below freezing in September or early October. As the autumn advances and the sun sinks, nights lengthen, and snow cover becomes more likely, it becomes possible to have sub-freezing days when 850mb temperatures are well above freezing, but early October is too early for that to happen.

7°F Beaver Creek RAWS

8°F Circle Hot Springs COOP

9°F Eagle airport and RAWS

9°F Chicken COOP

At Fairbanks airport the first indisputably hard freeze occurred the night before, with a low of 22°F. Yesterday was also the first day with a daily mean temperature of 32°F. If these conditions were to continue, it wouldn't be long before some ice would be running in the rivers, but the forecast shows a warming trend.

[Update October 5: this morning was colder, with a low of +1°F at the Chalkyitsik RAWS and +4°F at Chicken. Closer to Fairbanks, the Goldstream Creek COOP had 11°F, and it was 9°F at the Salcha RAWS.]

Speaking of the forecast, I couldn't help noticing a major discrepancy today between the GFS MOS (automated computer) forecast and the rest of the guidance for Fairbanks. Here's this morning's MOS bulletin, with the "N/X" line showing low temperatures well down in the teens from Thursday through Monday, and with high temperatures staying near or below freezing for several days despite clear skies.

A quick look at this evening's NWS forecast for the airport shows a dramatically different picture, with high temperatures above 40°F and lows not far below freezing.

The GFS model forecast itself (from which the MOS output is derived) shows increasing warmth aloft in the next week, with 850mb temperatures rising well above freezing by Friday, and with very low relative humidity suggesting clear skies.

The raw model 2m temperature forecast shows conditions similar to the NWS forecast and drastically different from MOS.

So what's going on with MOS? Frankly I have no idea, but it's clearly wrong - and this is interesting, because MOS usually serves as a baseline or "first guess" for forecast systems; it is generally much better than raw model output, because it's a statistical regression based on historical observations. I briefly wondered if perhaps MOS is assuming there is snow on the ground already, but this is most unlikely as the historical probability of having snowcover in Fairbanks at this date is less than 20%.

To show how unlikely it is that Fairbanks will see a daily high temperature below freezing any time soon, we can look at how cold the upper-air temperatures need to be to produce a sub-freezing day. The chart below shows the afternoon 850mb temperatures on all such days from September 20 through November 19, beginning in 1957; we can see that 850mb temperatures are always well below freezing when daytime conditions remain below freezing in September or early October. As the autumn advances and the sun sinks, nights lengthen, and snow cover becomes more likely, it becomes possible to have sub-freezing days when 850mb temperatures are well above freezing, but early October is too early for that to happen.

Saturday, October 1, 2016

Climate Observations - The Human Element

First off, I should quickly mention a significant temperature record yesterday at Barrow: the high temperature of 48°F was not only a record for the date, but the warmest on record for so late in the season. Previously the latest date with such warmth was September 24, 1995, when it reached 53°F. The late September 1995 heat wave was actually more unusual, though, as it reached 62°F in Barrow on the 22nd (and 78°F in Fairbanks the previous day).

And now for a different topic. I'm sure many readers are aware that daily maximum and minimum temperatures are automatically recorded by the ASOS observing platform at airports across Alaska, and these measurements generally go into the books unaltered as the "official" climate observations. This isn't always true, however; one reason is that sometimes the ASOS report is in error. There happened to be an example of this in Fairbanks this week, when the ASOS reported a 24-hour (midnight-to-midnight) high temperature of 59°F on Thursday, but in reality the high was only 51°F. Oddly the 6-hourly maximum temperatures reported by the ASOS (at 0, 6, 12, and 18 UTC) were correct for Thursday, but somehow the 24-hour maximum wasn't. The error was caught by NWS personnel and the climate record already shows the correct number.

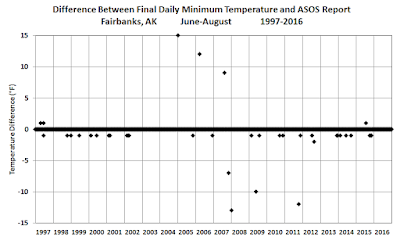

Looking back at the history of ASOS measurements in Fairbanks, it seems that manual adjustments to the ASOS data are not common, but neither are they rare. The charts below show the daily differences between the final "official" numbers and the ASOS reports for June through August. Curiously it seems that the daily low temperature is most often adjusted down by a single degree Fahrenheit. This didn't happen in summer 2016, but in August 2015 it occurred 4 times between August 10 and August 19.

It's strange and a bit unsettling to find that the ASOS temperature reports are apparently erroneous with some frequency, but in Fairbanks the errors are not large or frequent enough to cause significant differences in the long-term temperature averages; and in any case presumably the vast majority of the errors are noticed and corrected. The problem is intriguing, but it doesn't make a big difference in the grand scheme of things.

However, the same is not true of the data situation at Bettles - see the charts below. The maximum temperature differences show rather more frequent and significant changes, and the minimum chart is frankly shocking, with very frequent and mostly downward adjustments to the ASOS data, especially in recent years. Remarkably, in June-August of this year, the daily low temperatures were adjusted downward on 32 of 92 days, by an average of 3.3°F. In summer 2014, adjustments averaging 2.9°F were performed on 70 of 92 days. The question arises immediately as to whether this is an appropriate fix to a very bad ASOS problem, or whether the adjustments themselves are the problem.

The overall impact of the low temperature adjustments at Bettles is significant, as demonstrated in the chart below. In summer 2014, when the adjustments were greatest, the seasonal mean of daily minimum temperatures changed from 46.4°F to 44.2°F; this difference is comparable to the typical magnitude of changes from year to year.

So what is going on at Bettles? Well, I've learned that the FAA contract observer believes that the ASOS minimum temperatures are generally too high (at least in summer) and regularly adjusts them down, purportedly based on other thermometers. The adjustment is different from day to day and is often zero. From a scientific standpoint, this is difficult to accept, because a systematic error at the ASOS thermometer would show up all the time, not some of the time, and it would presumably affect daily maximum temperatures as well. NWS personnel have inspected the ASOS temperatures repeatedly on-site and have not uncovered a problem. Unfortunately there is nothing that can be done about the issue, because the FAA manages the observing program, and the accuracy of climate measurements are not a high priority for that agency.

Additional evidence indicating that the Bettles low temperature data have been corrupted can be found in a comparison of the official (airport) temperatures to the nearby SnoTel site at Bettles - see below. The SnoTel site runs much colder for overnight lows in summer, but the difference is consistent and the seasonal means are highly correlated from year to year. Notice, however, the trend towards smaller differences over time, as the official low temperatures have been adjusted downwards more often in recent years, and especially in 2014 and 2016. Remarkably, the differences between the two sites were smaller in every year from 2010-2016 than in any year from 2003-2009; there isn't much chance that this could happen at random, and accordingly the trend in the differences is statistically significant.

Here's what the chart would look like if the ASOS temperatures were left alone. There is still a slight trend towards smaller differences over time, but it's not statistically significant.

For additional context on ASOS errors, the daily temperature adjustments are shown below for McGrath. The situation there looks a lot more like Fairbanks, which suggests that this kind of frequency and magnitude of errors are typical. In contrast, the data adjustments at Bettles are highly atypical and (in my view) clearly erroneous; and this is quite unfortunate for the integrity of the long-term climate record in Alaska.

And now for a different topic. I'm sure many readers are aware that daily maximum and minimum temperatures are automatically recorded by the ASOS observing platform at airports across Alaska, and these measurements generally go into the books unaltered as the "official" climate observations. This isn't always true, however; one reason is that sometimes the ASOS report is in error. There happened to be an example of this in Fairbanks this week, when the ASOS reported a 24-hour (midnight-to-midnight) high temperature of 59°F on Thursday, but in reality the high was only 51°F. Oddly the 6-hourly maximum temperatures reported by the ASOS (at 0, 6, 12, and 18 UTC) were correct for Thursday, but somehow the 24-hour maximum wasn't. The error was caught by NWS personnel and the climate record already shows the correct number.

Looking back at the history of ASOS measurements in Fairbanks, it seems that manual adjustments to the ASOS data are not common, but neither are they rare. The charts below show the daily differences between the final "official" numbers and the ASOS reports for June through August. Curiously it seems that the daily low temperature is most often adjusted down by a single degree Fahrenheit. This didn't happen in summer 2016, but in August 2015 it occurred 4 times between August 10 and August 19.

It's strange and a bit unsettling to find that the ASOS temperature reports are apparently erroneous with some frequency, but in Fairbanks the errors are not large or frequent enough to cause significant differences in the long-term temperature averages; and in any case presumably the vast majority of the errors are noticed and corrected. The problem is intriguing, but it doesn't make a big difference in the grand scheme of things.

However, the same is not true of the data situation at Bettles - see the charts below. The maximum temperature differences show rather more frequent and significant changes, and the minimum chart is frankly shocking, with very frequent and mostly downward adjustments to the ASOS data, especially in recent years. Remarkably, in June-August of this year, the daily low temperatures were adjusted downward on 32 of 92 days, by an average of 3.3°F. In summer 2014, adjustments averaging 2.9°F were performed on 70 of 92 days. The question arises immediately as to whether this is an appropriate fix to a very bad ASOS problem, or whether the adjustments themselves are the problem.

The overall impact of the low temperature adjustments at Bettles is significant, as demonstrated in the chart below. In summer 2014, when the adjustments were greatest, the seasonal mean of daily minimum temperatures changed from 46.4°F to 44.2°F; this difference is comparable to the typical magnitude of changes from year to year.

So what is going on at Bettles? Well, I've learned that the FAA contract observer believes that the ASOS minimum temperatures are generally too high (at least in summer) and regularly adjusts them down, purportedly based on other thermometers. The adjustment is different from day to day and is often zero. From a scientific standpoint, this is difficult to accept, because a systematic error at the ASOS thermometer would show up all the time, not some of the time, and it would presumably affect daily maximum temperatures as well. NWS personnel have inspected the ASOS temperatures repeatedly on-site and have not uncovered a problem. Unfortunately there is nothing that can be done about the issue, because the FAA manages the observing program, and the accuracy of climate measurements are not a high priority for that agency.

Additional evidence indicating that the Bettles low temperature data have been corrupted can be found in a comparison of the official (airport) temperatures to the nearby SnoTel site at Bettles - see below. The SnoTel site runs much colder for overnight lows in summer, but the difference is consistent and the seasonal means are highly correlated from year to year. Notice, however, the trend towards smaller differences over time, as the official low temperatures have been adjusted downwards more often in recent years, and especially in 2014 and 2016. Remarkably, the differences between the two sites were smaller in every year from 2010-2016 than in any year from 2003-2009; there isn't much chance that this could happen at random, and accordingly the trend in the differences is statistically significant.

Here's what the chart would look like if the ASOS temperatures were left alone. There is still a slight trend towards smaller differences over time, but it's not statistically significant.

For additional context on ASOS errors, the daily temperature adjustments are shown below for McGrath. The situation there looks a lot more like Fairbanks, which suggests that this kind of frequency and magnitude of errors are typical. In contrast, the data adjustments at Bettles are highly atypical and (in my view) clearly erroneous; and this is quite unfortunate for the integrity of the long-term climate record in Alaska.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)